Self-Promotion

Thing is, writers who write the kind of fiction that’s hard for them to explain or contextualize or otherwise illuminate tend to have every bit as hard a time talking about themselves. Even as a little kid I supposedly used to say, “let it stand for itself” about my just-completed Lego constructions. And now that my castle or space station or whatever-the-hell-it-is is made out of tears and sweat and picked-clean bones, by which I mean only words? Forget it. But I wouldn’t have written Exes—a book about loss’s ever-present absence, about what’s no longer there—if it weren’t especially hard for me to talk about. Or as my mom, a painter, liked to say, “if what you’ve made doesn’t make you want to throw up, then it’s not art.” She also said art openings were like funerals—old friends standing around, measuring their words, signing the big black book by the door. My mom and my dad were the first artists I knew. But my mom was the first artist I knew who stopped making art, just like that. I used to think she had quit so she could get better, more stable jobs—which she did, eventually, and not coincidentally—but now I’m not so sure. I’d ask her, but she doesn’t like explaining herself, either. “Don’t talk about art,” she would always say, “talk art.” Which, like anything worth doing, is easier said than done—except, of course, for when doing it means saying it. It’s funny, because back when I first started writing, some well-meaning workshop members told me I shouldn’t write about artists because it was too easy. I didn’t know what to say. “If you say so,” I said. It was just how I grew up. But even so I made the suggested cuts.

Home

We moved into the second floor of the vinyl-sided triple-decker on Fourth after getting evicted from our place on Belair. I was three. There was a basement for my dad to paint in—he only ever gave up showing, sharing my mom’s dim view of openings: one of a precious few things on which they agreed—and an elm stump in the yard I would pretend was other, more-impressive things. Then at some point my mom stopped painting, and, one by one, her canvases disappeared from our apartment’s walls, either traded to friends for their paintings, or in one case for a truckload of chicken shit to fertilize a one-summer vegetable garden. Later, the Portuguese lady who moved downstairs would try to paint the stump white, to match her inside-out tire planter and the dooryard flowerbeds. For her that’s just what home looked like. White things got painted white, and so did brown things, like wood and dirt. One time my dad and I repainted a rock she had painted white back to rock-color.

FOR RENT

Ever since moving back to Providence in 2007—when I was almost halfway through what would become Exes—I’ve seen ‘For Rent’ signs out in front of the old tenement more times than I can count. Whenever I do, I think this will be the time I call the number and pretend to be looking, just to see the old place, or maybe the slant-ceilinged two-bedroom where the dudes upstairs would get into fistfights on weekends, or the first floor where the Portuguese lady and her son lived, and before her, the old man and his adult daughter, who both hated my mom for some reason, but who would also invite me over for candy when she wasn’t home. I don’t know why I never make the call; it would be easy. I only know I used to hate it when my parents would call the place a dump. When they did, they were mad about other things—work, money, painting—but also about the apartment. It only felt like home to me. But even so I didn’t invite friends—whose houses had real turrets and extra houses in back for cars and guests and tenants—over to my place until we moved into a two-bedroom bungalow a couple blocks closer to Pawtucket. But even then, only ever a couple close friends. Once the older sister of a less-close friend, whose parents were dropping me off at the bungalow, made a face at my block and said, “you live in a tenement?” I remember their sunken living room, how everything was perfectly white.

Supermarket Mittelschmerz

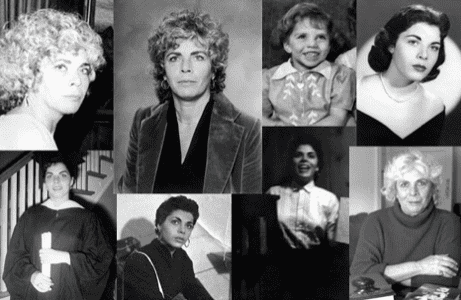

This was my favorite painting of my mom’s. It had hung above the kitchen table—which was also the dining room table, because where else would you eat?—until it suddenly didn’t. She had given it to an old friend who lived in New York and maybe knew Warhol. Years later—when I lived in New York, too—I called the guy up out of the blue and asked for the painting back. He said no. We were both pretty surprised, and the call lasted a minute at most. Part of me was just glad to hear the painting meant something to him. Based on his shocked reaction, it had to be up, at least. I can still see it: the floor of the titular market is green and the walls are black, I think. There are three women—one tall and thin, another short and wide, a third old and gray—all of whom simultaneously do and do not look like my mother. They look instead like how she felt then, or else how she thought she looked, but reflected in funhouse glass or when seen through someone wearing yet another person’s eyeglasses. Two of the not-my-mothers push empty carts. The market’s lone item is a blood-red t-bone, which sits unwrapped on a white counter in the foreground. I would stare up at the painting while eating breakfast, or picking at dinner. I wondered what they were looking for—these women—why they didn’t see the big red steak. About this, I no longer wonder.

Kodachrome

While writing this, I asked my mom if she had any photos of the supermarket painting. Only one slide remains—a fuzzy, uncomposed shot of the canvas leaning against that stump. Probably because of all the red, the grass looks weirdly green. The painting, however, looks exactly as I remember it. But my dad also found another, earlier slide, of a painting I’d never seen: a nude reclining on a couch in what appears to be a hotel in Miami Beach. The late afternoon sun falls on her through the window. In the background is a full tub. I asked my mom about it, and she said that during a critique, someone in her painting class had told her she really needed to study anatomy, so my mom later cut the canvas with scissors. We want it to be simple—why we do what we do and make what we make, and why we stop—but what’s simple? What’s easy? I can hear the blade piercing the canvas with a dry pop, can hear the tearing of fabric, the slicing of paint, but can’t picture it—can’t see my mother’s hand holding the scissors, pushing them down, cutting the woman in half.

❦❦❦