Pumps break. Positive displacement, diaphragm, piston, plunger, screw pumps. Progressive cavity pumps. Impulse, velocity, gravity pumps. Power pumps. Breast pumps. Those shoes with the tall slender heel, pumps.

And yet it’s always a surprise when the heart pump breaks.

But the heart is the only pump that grows stronger by way of its breaking.

There was a secret, jaded, pragmatic, implausible, heart-wrenching, compassionate part of me that knew the election of Hillary Clinton to the position of President of the United States of America would fail. Perhaps it was the very physicality of me that knew this, in my gut, in the synapses in my brain, in the physiology of my female body, in the protoplasm of me that could be grabbed.

I am queer, or in more specific if simpler terms, a sexual and gender minority. I consider myself most comfortably as a kind of middle gender. I have a faint blonde moustache and breasts that are too large, although if I’m going to be honest any breast is too much breast for me. Gray-blue eyes, short brown hair. I’m rarely catcalled by men, but often asked to leave the women’s bathroom.

Let me pause here and note just how completely terrifying it is that my brain just considered sexual harassment a benchmark of femininity. Is this patriarchy at war with my psyche? Did I conflate domineering masculine desire with some quality of the self or the body or did they? Is this me or them or us? If we are to consider ourselves one people, who are we? How does one locate, honor, and bridge the divide?

San Francisco, October 9th

I can’t say how many times, and in how many different ways, I’ve been told that emotionality equals weakness, that for survival you must bind your emotions. Leading up to the failed election I was emotional. Which in our current cultural convention places me walking the plank of womanness.

At the last debate, I could feel Clinton toeing the line of emotionality, could sense her veiled anger and disappointment that such a colossally corrupted man could have gotten to where she was, across the room on the debate floor. The injustice of it all. Despite this, Clinton was cool, strong, and in fact dominating.

I was watching at a dive bar in San Francisco, slouching on a bar stool, next to a dog wearing a bow tie, when she stopped the debate for a moment, redirected the conversation back to the Supreme Court, and said: The question was about the Supreme Court. And I just want to quickly say, I respect the Second Amendment. But I believe there should be comprehensive background checks, and we should close the gun show loophole, and close the online loophole.

Down the block there was a large funeral spilling out into the street. Just then someone took out a gun and shot another person outside on the corner. The dog began frantically barking. The bar owner closed the doors and told everyone to stay inside. I moved through them anyway. There was a man on the ground, breathing and bleeding. The thick blood pouring from his black body, discoloring the concrete. The sirens starting to wail somewhere off in the middle distance.

Why wouldn’t I be crying.

Philadelphia, November 6th

Knocking on doors in South Philadelphia the weekend before the election, I find myself grasping at a way to attach to hope. The neighborhood, one I’d lived in years before, is poverty stricken. Trash crowding the sidewalks, broken windows, street lamps hardly flickering above.

A woman calls down to me from her window. She’s just moved there, she says, she can’t come down now, she’s nursing, but if I could leave the information slipped under the door she’d much appreciate it. Behind one door is a young brown-skinned teenager. He says, Thank you, and listen tell my neighbors if they want a ride to the polls to knock on my door. There is a transit strike in Philadelphia, making it difficult for people to get to work, nevermind getting out to vote before or after work.

One door down a young man greets me at his screen door. His skin is dark, his eyes bloodshot. There’s a lightning bolt tattooed down his forehead. He is baby-sitting his four younger siblings and, no, he’s not registered to vote. I ask about his parents, and something sparks in his eyes. He says, You know what, write all that down for me. I’ll make sure they go.

And it becomes clear to me, like a flash of light in the cave, like the tattoo streaking down his forehead, that this young man’s conjuring of hope is contagious—and just like that, in that one moment of connection, he has gifted me mine.

Brooklyn, November 8th

The morning of the election I thought about what it means to vote for a woman. Voting for a woman felt like voting for respect, for tolerance, for justice, for peace, for empathy, for righteousness, for equality, for color, for movement, for understanding, for listening, for strength, for kindness, for hope, for openness, for braveness, for black lives, for gay rights, for emotion, for feeling, for spirit, for heart, for story, for making, for holding, for inclusivity, for love.

That night I watched the results come in at a friend’s restaurant, aptly named Hart’s, the kind of place brilliant with flavors and excessive kindness. Halfway through the evening my friend’s father, who is a pathologist from Chicago and had flown in to help that night, paused between running margaritas from table to table. He turned to me and said, God damn it, if this happens I’m going to become an abortionist.

The phrasing stopped me cold, my anxious heart pump pounding, my brain churning. An abortionist. Not an abortion doctor. An abortionist.

Brooklyn, November 9th

The morning after the failure of the election when I woke, I had a vision of standing in front of a gun, its muzzle pointed at my belly, at my womb, or maybe at the womb of a woman standing behind me, on her way to the open doors of a Planned Parenthood clinic. I thought of the words my friend and collaborator Millicent Souris wrote about being an escort at a Planned Parenthood in Chicago in the mid ’90s: The best thing to do in escorting a person into a health clinic is to offer focus. To make eye contact and go and meet her if necessary, if the sidewalk is flanked by people humming hymns and shouting “murderer.” Focus on me, look at me, I will help you get into these doors because when you woke up this morning you knew you were coming here, but you probably didn’t think this was going to happen.

When you grow up queer you learn quickly to whom and to what degree it is safe to reveal yourself. You learn to watch people, learn about them, and then to look them straight in the eye, not to challenge them, but to connect. It’s a strategy I’ve used to try and skip past all the various identities and surface impressions that might separate us, because it is in the chasm between those differences that the seed of violence, and to some degree, despair lies. Which is not to say I don’t honor those differences also, they are in fact a gift. But people want to be seen. They want to be experienced. They want to be beheld, almost as much as they want to be held.

Later that day at a lunch counter I witnessed the canyon between a mother and daughter open and almost swallow them both whole. The mother had just admitted to her gay daughter that she had voted for Trump. It was about abortion, the daughter whispered in my ear, as she shuffled to the door behind her mother. I watched as they helped each other with their coats, both of them challenged now with learning how to continue to love one another across a chasm of divided morality.

Houston, December 18th

In December I drive across the land of gamblers and oil men, winding through the large chalking red canyons, making my way past the green and white Border Patrol trucks of southern Texas. My companion and I stop at a gas station, just down the road from a Chevron Phillips Chemical plant, its ominous chemical pollutant flame licking at a dusty blue sky.

A white woman in the convenience store bathroom line, her arm in a sling, her daughter in the far stall, says to her friend, I’m glad our new president will bring my husband’s job back. She mutters something under her breath about Obama, calls him a name. Her eyes avoid mine. Hate lives in her voice like a demon she cannot shake. She is trying to comfort another woman, whose face burns red with booze, her husband also out of a job, her son idly wandering the candy aisle.

A black woman is mopping the store’s floor as they leave. I, and my gendered middleness, watch as both women pay for their gas, pay for candy, brush past the woman they do not even really see, climb into their SUVs, pull out onto Route 10.

What is it they say about a house that is burning?

Our attachment to privilege, to believing we are owed something, is not hope. It’s as if we are all in the grips of an addiction in which it’s too painful to remember what the sunrise feels like. It is what limits our vision, what led us to fail Hillary Clinton and each other in this election.

This failure leaves us on a planet that is dying around us and doing nothing about it. Where hosing down a human being with cold water in the freezing night is permissible. Where a young black man bleeds out on a San Francisco street alone. Because you, not them. Because safety, not empathy. Because I, not we. Because if I can just survive that’s enough.

But it’s not enough. It’s calcifying in the face of love.

I need to know about this America, not turn a blind eye to it, this America that I have forever been hesitant to love, have always in some untended chamber of my queer female heart feared would destroy me.

This was not an election about issues. This was not an election about good or evil either. It was an election about suffering. People are good, their souls are precious, their dreams are real and vital. This election illustrated for me how much and in what crushing amplitude people are suffering out there, and the way in which it is so easy when we are suffering to attach ourselves to and be motivated by hate. How hate creates a shell that eclipses our morality, our humanity, our joy, our dignity.

This election made me feel the need to protect people, and that breaks my heart pump.

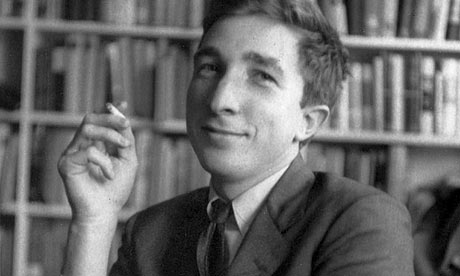

James Baldwin said, If you can’t love anybody you are dangerous. You have no way to learn humility, no way to learn that other people suffer and to use your suffering and theirs to get from this place to that.

And so I challenge myself and all of us to push beyond our disappointment and heartbreak, beyond our attachment to power as a means of survival, beyond loving anybody to loving everybody. Listen, I am angry. And, yes, in many ways I have become a canvas of rage. But anger is different than hate. I will use my anger to activate, to demonstrate, to make phone calls, to learn to love harder and stronger.

And, yes, to march this weekend.

We may be without compass and the road is dark and full of raving ghosts and unimaginable obstacles. But we will move forward—with our more expansive, our stronger hearts. We will heal. We will grow. We will dance when we can, and hold on to one another, we will make food for those of us who are hungry, we will listen for the sorrow of others, we will witness and cherish and see each other, and we will be devastated, but fearless in the face of hatred.

We will carry those who need to be carried.

That’s what women do.

And we must all be women now.